Phillip Danforth Armour (1832-1901) is today remembered only for the meatpacking company he founded, but in his own time was lauded for allegedly contributing to the progress of civilization by moving animal slaughter out of sight, smell, and sound of women, children, and decent men.

Born into an upstate New York farming family, Armour drove barge-hauling mules alongside the Chenango Canal in his teens, then walked all the way to California at age 19 to join the Gold Rush. He soon discovered that more gold was to be made by starting a Placerville butcher shop than in mining.

Returning east with savings of $8,000, Armour founded a pig slaughtering business in Milwaukee in 1867, moved it to Chicago, and within 20 years was killing more than 1.5 million pigs and cattle per year. Though others shared in the invention of high-speed, high-volume mechanized slaughter, Armour more than anyone else is credited with conceptualizing the "disassembly line," leading to the rise of industrial slaughter.

This was considered a significant advance for many reasons beyond merely making meat more accessible and affordable to urban Americans. Concentrating stockyards and slaughter at a single location served by railways helped to make cities more tolerable places to live than when livestock were driven through the streets, the odors and screaming of animals assailed senses and sensibilities in every neighborhood, blood flowed through the gutters, and offal heaps were dumped for dogs and pigs to scavenge in vacant lots and alleys–as continues in much of the developing world. The term "shambles" originated in 16th century Britain to describe the place where slaughter was done, and remains a common description of disreputable properties.

Removing slaughter from the local commercial districts serving residential neighborhoods also removed slaughtermen, whose working practices and recreational pursuits, including brawling, public drunkenness, and gambling on animal fights, had already been widely decried by humanitarian reformers for more than a century before Armour's time. Bull-baiting, in particular, had evolved directly from the medieval European practice of using bulldogs to hold cattle while their throats were cut, and contributed to the development of dogfighting. Cockfighting was also a "sport" of butchers and their suppliers. Though gambling and animal fights had been banned in many communities since Puritan times, they tended to remain ubiquitous until after slaughter was banished to the margins of cities.

Phillip Armour toward the end of his life attracted the fawning attention of Orison Swett Marden (1850-1924), a prolific author of self-help books. "It is after business hours, not in them, that men break down," asserted Marden in Cheerfulness as a Life Power (1899). "Men must, like Philip Armour, turn the key on business when they leave it, and at once unlock the doors of some wholesome recreation."

Marden wrote of how Armour personally distanced himself from slaughter at the very height of the 1898-1899 tainted beef scandal involving the Armour slaughter empire that inspired Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) to author The Jungle, a novelized exposé of the slaughter industry published in 1906, five years after Armour's death.

Observed Sinclair, "Men who have to crack the heads of animals all day seem to get into the habit, and to practice on their friends, and even on their families, between times. This makes it a cause for congratulation that by modern methods a very few men can do the painfully necessary work of headcracking for the whole of the cultured world."

Industrializing the mayhem moved it out of the daily experience of most people, but scarcely changed the psychological effects of killing animals, quantified in our own time by Amy J. Fitzgerald of the University of Windsor and Linda Kalof and Thomas Dietz of Michigan State University in a 2009 study entitled Slaughterhouses and Increased Crime Rates: An Empirical Analysis of the Spillover From "The Jungle" Into the Surrounding Community, published in the journal Organization & Environment.

"More than 100 years after Upton Sinclair denounced the massive slaughterhouse complex in Chicago as a 'jungle,' qualitative case study research has documented numerous negative effects of slaughterhouses on workers and communities," Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz opened. "Of the social problems observed in these communities, the increases in crime have been particularly dramatic. These increases have been theorized as being linked to the demographic characteristics of the workers, social disorganization in the communities, and increased unemployment rates. But these explanations have not been empirically tested, and no research has addressed the possibility of a link between the increased crime rates and the violent work that takes place in the meatpacking industry."

Therefore Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz did a complex set of statistical comparisons of the demographic variables in 581 counties from 1994 to 2002, compared to the FBI's Uniform Crime Report database. "The findings," they concluded, "indicate that slaughterhouse employment increases total arrest rates, arrests for violent crimes, arrests for rape, and arrests for other sex offenses in comparison with other industries. This suggests the existence of a 'Sinclair effect' unique to the violent workplace of the slaughterhouse, a factor that has not previously been examined in the sociology of violence."

Findings parallel hunting studies

Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz used similar methods and some of the same raw demographic and crime data that ANIMAL PEOPLE used in a 1994-1995 set of comparisons of hunting license sales with child abuse convictions in the 232 counties of New York state, Ohio, and Michigan. The initial study, covering the 62 counties of New York state, found that in 21 of 22 direct comparisons between counties of almost identical population density, the county with the most hunters also had the most child molesting. Twenty-eight of the 32 New York counties with rates of child molesting above the state median also had more than the median rate of hunting. The second ANIMAL PEOPLE study demonstrated that among the 88 counties of Ohio, those with more than the median number of hunters per 100,000 residents had 51% more reported child abuse, including 15% more physical violence, 82% more neglect, 33% more sexual abuse, and 14% more emotional maltreatment. The third ANIMAL PEOPLE study found that Michigan children were nearly three times as likely to be neglected and twice as likely to be physically abused or sexually assaulted if they lived in a county with either an above average or above median rate of hunting participation.

ANIMAL PEOPLE concluded that the parallels prevalent in all three states support a hypothesis that both hunting and child abuse reflect the degree to which a social characteristic called dominionism prevails in a particular community. Stephen Kellert, in a 1980 study commissioned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in part to discover effective defenses of hunting, defined dominionism as an attitude in which "primary satisfactions [are] derived from mastery or control over animals," a definition which other investigators extended to include the exercise of "mastery or control" over women and children. Kellert–a hunter who for 30 years has struggled to deny the import of his findings–reported that the degree of dominionism in the American public as a whole rated just 2.0 on a scale of 18. Humane society members rated only 0.9. Recreational hunters, however, rated from 3.8 to 4.1, while trappers scored 8.5.

Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz found much the same tendencies in their study of slaughtering and crime, including "sexual attacks on males, incest, indecent exposure, statutory rape, and 'crimes against nature,'" they reported. "Many of these offenses are perpetrated against those with less power," Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz noted. "We interpret this as evidence that that the work done within slaughterhouses might spillover to violence against other less powerful groups, such as women and children.

"The use of the term spillover here derives from the cultural spillover of violence theory developed by Larry Baron and Murray Straus (in 1987-1988)," Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz explained. "The central tenet of this theory is that the more a society tends to endorse the use of physical force to attain socially approved ends-such as order in the schools, crime control, and military dominance–the greater the likelihood that this legitimization of force will be generalized to other spheres in life, such as the family and relations between the sexes, where force is less approved socially. Although the authors did not specifically discuss the slaughter of animals as part of this process, we argue that it is a possibility."

Concluded Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz, "The results presented here therefore demonstrate significant and unique effects of slaughterhouse employment on several crime variables. These effects are not found in [other industries with a demographically comparable workforce], and they cannot be explained by unemployment, social disorganization, and demographic variablesŠIn particular, our results lend support to the argument, first articulated by Sinclair, that the industrial slaughterhouse is different in its effects from other industrial facilities. We believe that this is another of a growing list of social problems and phenomena that are undertheorized unless explicit attention is paid to the social role of nonhuman animals."

Temple Grandin found hints

Ironically, much as research meant to help promote hunting produced hints pointing toward the association of hunting with crimes against children, research commissioned by the slaughter industry pointed more than 20 years ago toward the association of slaughter with violent crime and crimes of sexual exploitation.

Summarized Colorado State University professor of psychology and animal science Temple Grandin in her 1988 Anthrozoos commentary Behavior of Slaughter Plant & Auction Employees toward the Animals, "Abuses of animals at auctions and slaughter plants occur often. In 1984, an investigator was hired to make unannounced visits on sale day at 51 livestock markets in 11 southeastern statesŠ32% had either rough handling or acts of cruelty. Twenty-five federally inspected U.S. and Canadian slaughter plants were visited by the author between 1975 and 1987," at which eight had "acts of deliberate cruelty occurring on a regular basis." At three others Grandin observed "rough handling occurring as a routine practice."

Found Grandin, "Approximately 4% of the employees directly involved with livestock committed acts of deliberate cruelty," while "In some poorly managed plants and auctions over half the employees engaged in rough treatment of animals. Personal observations indicate that severe rough handling, abuse, and neglect on farms, ranches, markets, and feedlots have remained at a steady 10% to 15% of operations for the last ten years over the entire United States."

Grandin was optimistic, based on results from slaughterhouses where she was able to personally initiate programs to reduce sadism and rough animal handling, that the problems she saw could be remedied. But Grandin noted psychological tendencies among slaughter workers which had been familiar to Sinclair–and probably to Armour, whose habit of distancing himself from his work after business hours Marden approvingly cited.

"The most common management psychology is simply denial of the reality of killing," observed Grandin. "Managers will use words such as 'dispatching' and 'processing' to avoid this reality. The people who actually do the killing in slaughter plants have three different approaches to their jobs. These are the mechanical approach, the sadistic approach, and the sacred ritual approach. These approaches usually are observed only in the people who actually do the killing or who drive the animal up the chute. The mechanical attitude is most common. The person doing the killing approaches his job as if he was stapling boxes moving along a conveyer belt."

Recommended Grandin in conclusion, "It is important to rotate the employees who do the killing, bleeding, shackling, and driving. Nobody should kill animals all the time. Several plant managers and supervisors state that rotation helps prevent employees from becoming sadistic. The author has worked many full shifts driving livestock and operating the kill chute at slaughter plants. Rotation every few hours between the kill chute and driving cattle up the chute made it easier to maintain a humane attitude. It is also easier to maintain a good attitude in plants with a slower line speed. At 1,000 hogs per hour it is almost impossible to handle the hogs properly. The constant pressure to keep up with the line leads to abuse. Maintaining respect for animals is much harder at 1,000 hogs per hour compared to 500 hogs per hour."

But even Armour's slaughter lines worked at what would now be considered very slow line speeds. At slower line speeds, employees may be able to work more precisely, causing less suffering to each animal they kill, if they make this a priority, but the underlying psychological issue is still the cumulative effect of taking lives, at whatever speed and in whatever environment.

The butchers who used bulldogs at the London shambles when the Royal SPCA was founded in 1824 usually killed just one or two animals per day. Recreational deer hunters typically kill only one or two animals per year, yet the association of hunting with spillover into violence against children was starkly clear in the ANIMAL PEOPLE studies.

Ultimately the question is whether killing animals can ever be done without emotional consequence to those who do the killing, regardless of the purpose and regardless of the approach of the person doing the killing.

Phil Arkow in The Humane Society & the Human Animal Bond: Reflections on the Broken Bond (1985) quantified the psychological effects of killing dogs and cats on shelter workers. Killing nearly five times more dogs and cats then than now, shelter workers mostly took what Grandin described as the "sacred ritual approach," and still do.

Shelter workers have rarely ever been involved in violent crimes against anyone else, but in the mid-1980s had rates of alcoholism, other substance abuse, clinical depression, and suicide comparable to those of Vietnam War combat veterans. The introduction of psychological counseling programs for shelter workers may have helped, but post-traumatic stress among shelter workers has receded mainly coincidental with shelters killing far fewer animals.

There is now widespread public recognition that killing fewer dogs and cats at animal shelters, for whatever cause, is an indication of progress toward becoming a healthier society, in which life and well-being are more highly valued.

There is also increasingly broad public recognition of the need to improve the welfare of farmed animals, indicated by the success of pro-farm animal welfare ballot initiatives, petitions seeking to place more such initiatives before voters, and expanding commercial interest in labeling products as humanely produced.

Though many of these measures fall disappointingly far short of achieving the substantive improvements they promise, that they are advancing at all is a remarkable turnabout from the century-plus of "out of sight, out of mind" attitudes toward farmed animals that Phillip Armour introduced.

Yet most of humanity has not so far recognized that killing fewer animals to eat–or best, none–would also contribute to becoming a healthier society, both physically and psychologically. Much research, before Fitzgerald, Kalof, and Dietz, pointed toward positive effects on physical health from not eating animals. Now studies of the societal health effects of killing animals as an industry have begun.

As academic papers stereotypically conclude, "More study is necessary," since no one study will sway the world. But relevant questions are at last under examination.

Veteran journalist Merritt Clifton serves as editor in chief of ANIMAL PEOPLE, the only professional, independent publication devoted to the coverage of ecoanimal issues.

P.O. Box 960

Clinton, WA 98236

Telephone: 360-579-2505

______________________________________________

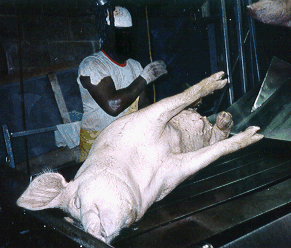

Picture credits: Gail Eisnitz & Compassionate Action for Animals

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.